The Women Behind the Cameras in Early Hollywood

BY JUDY CARMACK BROSS

“I now have 1000 names of women—producers, director, editors, and writers—who worked behind the cameras in silent films, representing 1000 stories never told,” says Dwight Cleveland, who will be speaking May 6 in New York City, where his one-of-a-kind collection of lobby cards from the silent movie era is on exhibit until October 9.

Cleveland’s talk at the Poster House in New York is one of several scheduled on “Experimental Marriage: Women in Early Hollywood.” While doing research for his monumental book on movie posters, Cinema on Paper, he first became intrigued with the topic that has now broadened to include other under-represented populations in the early movie industry: “The unregulated, non-unionized status of the burgeoning field during the 1910s and ’20s meant that there were fewer barriers to entry,” he explains. “This allowed women the opportunity to excel both on and off camera, particularly on the coasts in California, New York, and New Jersey where new cinema hubs were being created.”

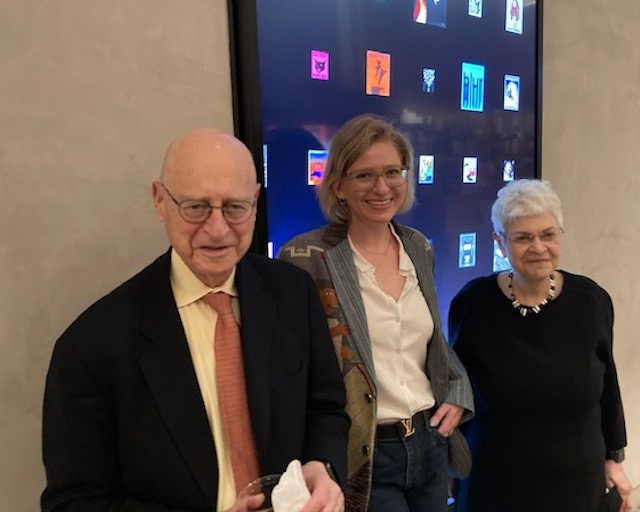

Salvador Muñoz, Public Programs Manager at Poster House; Melissa Walker, Curator of Experimental Marriage; and Dwight Cleveland at Poster House.

He happened to stumble upon Dorothy Arzner, whose career began in the silent movies and onto becoming the first woman to direct a talking picture. “While checking on her name in the online database IMDb, I began clicking on other names and went on to discover women like Cosmopolitan magazine writer Fannie Hurst; screenwriter Frances Marion; actress, director Jeanie McPherson; and many more. It all snowballed,” Cleveland recalls.

Frances Marion authored over 325 scripts and was the first writer to win two Academy Awards. She wrote several silent scripts for her best friend Mary Pickford before transitioning to talkies. She was also a director and an author of stage plays and novels, as well as a combat correspondent during World War I. She supposedly dropped out of school at age 12 after drawing a comic strip about her teacher.

Cleveland says if it weren’t for the time in isolation during COVID, he never would have embarked on his research: “We were not going out to dinner, the phone wasn’t ringing, and I dug into the project, which would involve enormous blocks of time. I was not interested in movie stars but those behind the camera.”

He soon found the Women Pioneers Project done by Jane Gaines at his alma mater Columbia University—she had 208 names on her list. IMDb revealed even more. “I decided to focus on those in the United States and discovered that there were thousands of movies having been made by these women. The poster field is a small one and through my collecting, I know what the key players have in their collections. Armed with this list, I decided to go to a friend who has a collection of 25,000 lobby cards. I said that I wanted to buy 500 the first day I looked through them, then by the fourth day, there were 4500 in my piles. By the sixth day, I had gone through all of them. In the end he said he would cut me a deal for all 25,000, and I bought the entire collection.”

Cleveland’s children, with his wife, Gabriela, are now grown, so luckily the playroom was empty of sports equipment and long empty of Legos and other toys, and the 25,000 lobby cards could be housed in that space.

And so, Cleveland could begin to build his database. “My daily schedule was the same for many weeks: up at 5:30 a.m., working until 10:00 p.m. when I couldn’t go any further. Gabriela would come by to insist I at least eat lunch,” he remembers.

“In the end I had pulled out 9500 items, eliminated any duplicates, and now have about 8750. In the beginning it was about women, but now I have also pulled out for my collection lobby cards about all underrepresented people working during the silent era. I know the major lobby card collectors in the world and what is in their collections. They are like vacuum cleaners pulling in all that’s out there. I am convinced that no one could come close to my collection. The show at Poster House is a niche exhibition, hopefully to be seem in other locales,” he says. A self-described “movie geek,” Cleveland has been collecting posters for 45 years.

Why silent movies? “The acting is what makes it so different,” Cleveland shares. “It gives people the chance to see actors communicate without words. You should take time to really watch it. For the audience at that time, it was so engaging to be there in the dark with other people—what they saw was captivating.”

Cleveland himself was first drawn in by the short comedies made by Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton: “These were no more than 15 minutes long, and they caught you from the beginning. In both the silent and talking films, Greta Garbo was one of the most captivating actors of all time.”

BAB’S DIARY (1917), Margaret Turnbill (scenario), Mary Roberts Rinehart (story), Martha D. Foster (writer), Marguerite Clark (star).

“When I first discovered the huge number of women behind the cameras in silent movies, I inched my way along. What an impact these women made on silent movies,” he reflects. “Jane Gaines is holding a conference in New York in June and I will be making one of the presentations. People will be coming from all over the world because of their interest in the accomplishments of these women pioneers in the movies.”

“Experimental Marriage: Women in Early Hollywood” will take place Friday, May 6, from 6:00–9:00 p.m. at Poster House, 119 West 23rd Street in New York. The show, currently on view, closes October 9. Visit posterhouse.org for more information on the exhibition and to buy tickets. To learn about the Women and the Silent Screen Symposium in June, hosted by Jane Gaines at Columbia University, click here and here. Visit cinemaonpaper.com for more on Cleveland’s exceptional book.