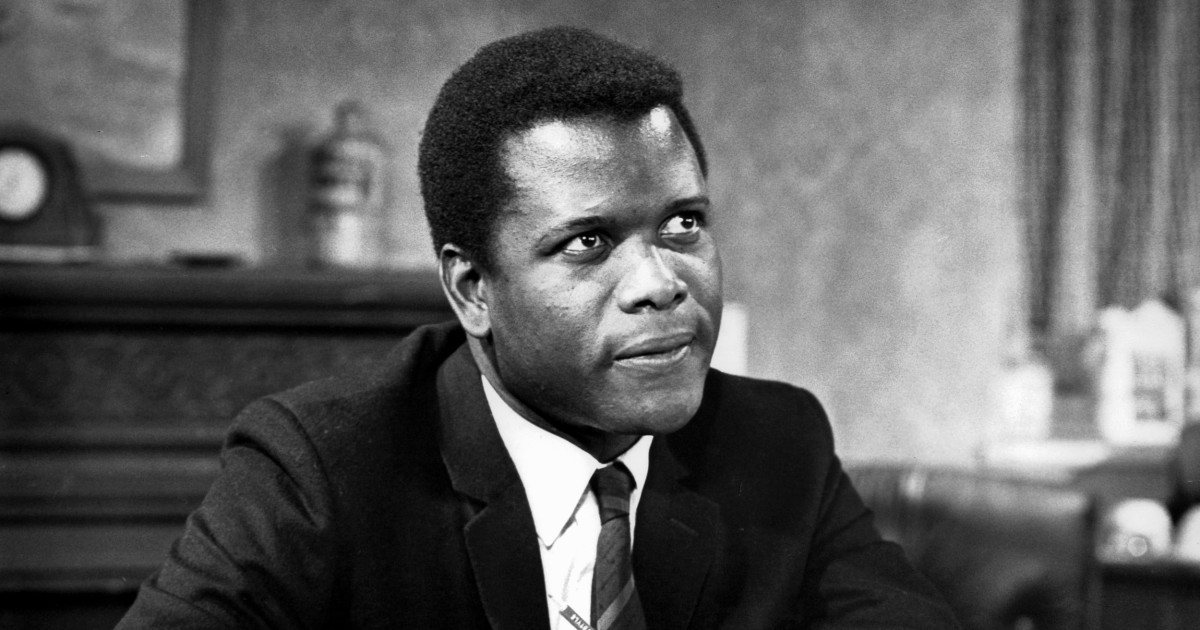

Sidney Poitier, trailblazing Hollywood icon who broke barriers for Black actors, dies at 94

Sidney Poitier, the renowned Hollywood actor, director and activist who commanded the screen, reshaped the culture and paved the way for countless other Black actors with stirring performances in classics such as “In the Heat of the Night” and “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” has died, a source close to the family told NBC News on Friday.

He was 94. The actor’s cause of death was not immediately given.

“Sir Sidney’s light will continue to shine brightly for generations to come,” said Philip Davis, the prime minister of the Bahamas, where Poitier grew up.

In a groundbreaking film career that spanned decades, Poitier established himself as one of the finest performers in America. He made history as the first Black man to win an Academy Award for best actor and, at the height of his fame, he became a major box-office draw.

Poitier, who rejected film roles based on offensive racial stereotypes, earned acclaim for portraying dignified, keenly intelligent men in 1960s landmarks such as “Lilies of the Field,” “A Patch of Blue,” “To Sir, With Love,” “In the Heat of the Night” and “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner.”

He said he felt a responsibility to represent Black excellence at a time when the vast majority of movie stars were white and many Black performers were relegated to subservient or buffoonish roles. He came to be seen as an elder statesmen in the film industry, celebrated for his social conscience and admired for his regal bearing.

“I felt very much as if I were representing 15, 18 million people with every move I made,” Poitier once wrote about the experience of being the only Black person on a movie set.

He won the best actor Oscar in 1964 for his depiction of an ex-serviceman who helps East German nuns build a chapel in “Lilies of the Field.” The first Black man to win that honor, he remained the only one until Denzel Washington in 2002 — the same year Poitier received an honorary Oscar “in recognition of his remarkable accomplishments as an artist and as a human.”

“I’ll always be chasing you, Sidney. I’ll always be following in your footsteps,” Washington said in his Oscars acceptance speech. “There’s nothing I would rather do, sir.”

In the course of his public life, Poitier was the recipient of the Kennedy Center Honors in 1995, the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2009, two Golden Globe awards (including a lifetime achievement honor in 1982), and a Grammy for narrating his autobiography, “The Measure of a Man: A Spiritual Autobiography,” published in 2000.

“Through his groundbreaking roles and singular talent, Sidney Poitier epitomized dignity and grace, revealing the power of movies to bring us closer together,” Obama said in an Instagram post. “He also opened doors for a generation of actors. Michelle and I send our love to his family and legion of fans.”

Poitier was born prematurely Feb. 20, 1927, in Miami, to Bahamian parents while they were on vacation in the United States. He grew up in the Bahamas, spending his early years around his father’s tomato farm on Cat Island before the family relocated to Nassau. The teenage Poitier returned to the U.S., where he enlisted in the U.S. Army and briefly served in a medical unit.

He eventually made his way to New York City and discovered a passion for the performing arts. He applied to the American Negro Theatre, but he was rejected because of his accent, so he spent the next several months practicing American enunciation. When he re-applied, he was accepted into the company and, in 1946, he made his Broadway debut in “Lysistrata.”

Poitier made his feature debut in the 1950 film noir “No Way Out” and the following year appeared in “Cry, the Beloved Country,” a British film set in apartheid-era South Africa. He gained greater attention in the 1955 drama “Blackboard Jungle” as a troubled but musically gifted student at an inner-city high school.

He broke through in 1958 with “The Defiant Ones,” teaming up with Tony Curtis for the tale of two escaped prisoners forced to survive while shackled together. The film was a critical smash, and Poitier and Curtis were both nominated for best actor Oscars. (They lost to David Niven for “Separate Tables.”)

“The Defiant Ones” opened up exciting career opportunities for Poitier. He drew praise as the crippled beggar Porgy in Otto Preminger’s musical “Porgy and Bess” (1959), adapted from the George Gershwin opera, and the determined Walter Lee Younger in “A Raisin in the Sun” (1961), adapted from the Lorraine Hansberry play.

In the 1960s, Poitier leveraged his Oscar win for “Lilies in the Field” and his growing national celebrity. He refused roles based on racist caricatures and gravitated to films that celebrated the main character’s dignity, grace, intellect and honor.

When he started acting, he said in a 1967 interview, “the kind of Negro played on the screen was always negative, buffoons, clowns, shuffling butlers, really misfits. This was the background when I came along 20 years ago and I chose not to be a party to the stereotyping.

“I want people to feel when they leave the theater that life and human beings are worthwhile,” Poitier added. “That is my only philosophy about the pictures I do.”

“A Patch of Blue,” released in 1965, was a pathbreaking portrait of the relationship between Poitier’s educated office worker and Elizabeth Hartman’s blind white woman. The film further established him as one of the key leading men in Hollywood.

Two years later, in 1967, Poitier went on one of the most incredible runs of his career. He played a tough but compassionate school teacher in “To Sir, With Love,” Philadelphia detective Virgil Tibbs in the Southern crime drama “In the Heat of the Night,” and a widower engaged to the daughter of white San Francisco liberals in “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner.”

The three films addressed race relations with varying degrees of intensity. “In the Heat of the Night,” anchored by Poitier’s galvanizing performance (“They call me Mister Tibbs!”), won the best picture Oscar. “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” filmed when interracial marriage was still illegal in many states, was one of the few at the time to depict interracial love favorably.

Poitier’s work from the period drew its share of criticism, however. “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” released as the American film history was on the cusp of a stylistic revolution (“Easy Rider,” “The Graduate,” and so on), struck some viewers as instantly dated and square. Poitier, for his part, was sometimes faulted for playing idealized characters with few personal foibles.

In the early 1970s, Poitier went behind the camera. He made his directorial debut with the Western “Buck and the Preacher” (1972) casting himself alongside Harry Belafonte and Ruby Dee. Poitier directed Belafonte again in “Uptown Saturday Night,” where they were joined by comedian Bill Cosby.

Poitier went on to direct Cosby in “Let’s Do it Again” (1975), “A Piece of the Action” (1977), and the family-geared misfire “Ghost Dad” (1990).

Poitier stepped away from acting for much of the 1980s, although he directed the hit Gene Wilder-Richard Pryor buddy comedy “Stir Crazy” (1980) and cast Wilder again two years later for “Hanky Panky,” co-starring “Saturday Night Live” alum Gilda Radner.

In the late 1980s, Poitier returned to acting, cropping up in “Shoot to Kill” and “Little Nikita,” both released in 1988. He delivered a memorable supporting turn in the cult comedy “Sneakers” (1992), and he went on to play Thurgood Marshall and Nelson Mandela in made-for-TV movies.

By the 2000s, Poitier effectively retired from screen acting, but he remained creatively productive. He published the autobiography “The Measure of a Man” in 2000; a follow-up book, “Life Beyond Measure: Letters to My Great-Granddaughter,” in 2008; and a novel, “Montaro Caine,” in 2013.

He served as the Bahamian ambassador to Japan for a decade, from 1997 to 2007, and he continued to inspire young talent across the performing arts.

“What a landmark actor,” the actor Jeffrey Wright tweeted. “One of a kind. What a beautiful, gracious, warm, genuinely regal man. RIP, Sir. With love.”

Poitier is survived by his wife, Joanna Shimkus, a retired actress from Canada; and five daughters: two — Anika and Sydney Tamiaa — with Shimkus; and three — Beverly, Pamela, and Sherri — with his first wife, Juanita Hardy. His daughter Gina died in 2018.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this obituary misstated the number of Sidney Poitier’s surviving daughters. He is survived by five daughters, not six (his daughter Gina died in 2018).