‘CODA’ Oscars win should usher in a new era of inclusion

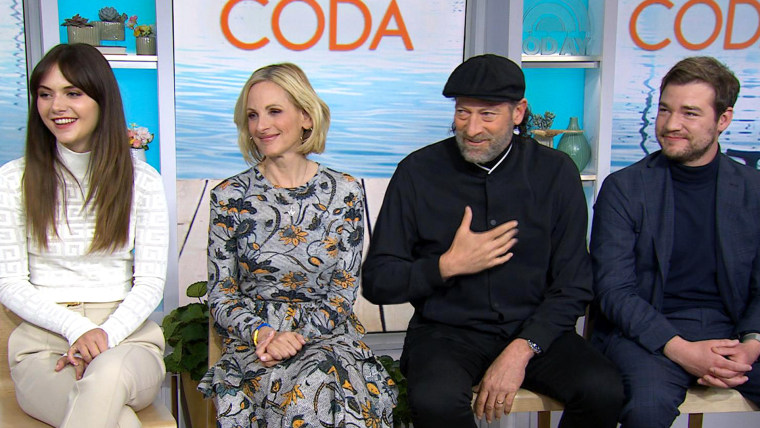

“CODA,” a movie that featured deaf actors portraying deaf characters, was the surprising winner of the Oscar for best picture Sunday night. The rave reviews and the film’s other awards — including Oscars for Troy Kotsur for best supporting actor and Sian Heder for best adapted screenplay — were already incredibly encouraging, but “CODA” taking home the biggest prize on Hollywood’s biggest stage ought to give the industry more incentive to produce movies by, for, about and with people with disabilities.

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences has a long history of rewarding poor portrayals of disability.

“CODA” chronicles the Rossis, a family in Massachusetts in which the wife, husband and son are all deaf but the daughter, Ruby, is the only hearing member, who learns she has a talent for singing. That leads to her working to apply to Berklee College of Music.

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences has a long history of rewarding poor portrayals of disability. It has rewarded Dustin Hoffman, Eddie Redmayne, Daniel Day-Lewis and Tom Hanks, abled-bodied actors who all, all at one point or another, have been rewarded for “cripping up,” that is, portraying disabled characters. In recognition of Hollywood’s disrespect of disabled people, Jim Sheridan, who directed the film “My Left Foot,” for which Day-Lewis earned his Oscar, has said he would cast a person with a disability if the film were made today.

I’ve written in this space before about the need for Hollywood to better portray people with disabilities. Given the success of the 2020 documentary “Crip Camp” and the backlash last year to “Music,” Sia’s reductive and harmful portrayal of autism, there seems to be more of an appetite for such movies. But the entertainment industry has been slow to make movies that accurately and wholly portray people with disabilities.

To be clear, “CODA” isn’t perfect, and the Deaf community has its critiques. Jeanna Beacom has said “CODA” doesn’t accurately portray deaf adult experiences. Another repeated criticism is that, among the characters, there are no other interpreters except daughter Ruby, the sole hearing member in a family when interpreters would be legally required by the Americans with Disabilities Act for the Rossis’ fishing boat, as well as for a court hearing. For what it’s worth, I think the absence of more interpreters could have been used to show how often people with disabilities don’t get the services to which they’re entitled, and that could have been contrasted with the fact that the family works in an overregulated fishing industry that doesn’t provide them the legal protections they need to thrive. Every person with a disability has dealt with this indignity and knows that it makes work harder.

The Deaf community has every right to voice its concerns, especially because “CODA” is one of the first major movies about a deaf family. Personally — as an autistic hearing person — I cringed at the decision to have the deaf father, played by Kotsur, verbally tell his daughter “Go” as she heads off to college because it suggests spoken words are more valid than signed words. In the back of my mind, I worried that the academy factored that scene into its judgment when it voted to give him the award, even as he gave a loving signed tribute to the disability community in his acceptance speech.

The only way to get better movies with people with disabilities is for the industry to keep making them.

We might expect “CODA” to be an imperfect portrayal of the disabled experience, especially since the entertainment industry has not done many similar movies. The only way to get better movies with people with disabilities is for the industry to keep making them until their portrayals become more natural. As for “CODA,” I personally appreciate the film’s portrayal of people with disabilities having fulfilling love and sex lives because for far too long, disabled characters have been portrayed as eunuchs.

As we celebrate “CODA” winning best picture Oscar, we need to remember that everything had to go right for the film to win. Apple TV hosted it on its streaming service, which gave it the right kind of backing, and The Wall Street Journal estimated that Apple spent about $10 million campaigning for it to win Oscars. Most disabled creators don’t have such good fortune.

“CODA” also had a major star in Marlee Matlin, the only openly disabled actress to have won an Oscar, and not only was her casting sure to attract viewers, but Matlin also used her leverage and threatened to pull out of the movie if other deaf actors were not cast. “Deaf is not a costume,” she said. She’s right. No disability is. A cast of deaf actors gave “CODA” a realism hearing actors could not possibly have replicated, which, in turn, made for an even better movie.

But of course, the film business is just that, a business. It needs the right kind of motivation, which is to say awards, which bring viewers, which bring dollars. Now, the business will see that disabled stories can be just as profitable as other ones and earn just as many accolades. The question is whether the wins of “CODA,” as IndieWire’s Kristin Lopez said, means more talented actors, like Kotsur, will be offered outside those solely made for people with disabilities.

Far too often, people use ableist cliches such as “falling on deaf ears” or “turning a blind eye.” But that’s inaccurate and offensive; deaf people aren’t choosing not to hear; neither are blind people choosing not to see.

But for far too long, Hollywood has deliberately chosen to act as if disabled people don’t exist as characters, creators, viewers or actors. The wins for “CODA” are big, but it won’t mean much if Hollywood goes back to its old, oblivious ways.