How Eve Babitz Saw Herself

Eve Babitz was one of the truly original writers of 20th-century Los Angeles: essayist, memoirist, novelist, groupie, feminist, canny ingenue. By the time of her death at the end of last year, she was enjoying a renaissance. Two essay collections, Eve’s Hollywood and Slow Days, Fast Company, were back in circulation; I Used to Be Charming, a gathering of previously uncollected pieces, was released in 2019. That same year, Lili Anolik published her deliciously fangirlish biography, Hollywood’s Eve: Eve Babitz and the Secret History of L.A. A half-century after her major-magazine debut at Rolling Stone, Eve Babitz was being introduced to a new generation of readers by writers who had sharpened their craft by reading her.

If you know only one thing about Eve Babitz, it’s probably that in 1963, at the age of 20, she was photographed at the Pasadena Art Museum playing chess with Marcel Duchamp—in the nude (elle, not il). In March of this year, the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, less than four miles from the venue of that chess match, announced the acquisition of the Babitz archive—a few dozen bankers boxes of manuscripts, original works of art, journals, photographs, and correspondence.

I was lucky enough to be granted early access to the archive. A longtime admirer of Babitz’s work, I could hardly believe my good fortune. As a teenager, my point of entry was her writing about rock and pop: If you know only two things about Babitz, the second is probably that she’s the L.A. woman in the Doors song. (One of the archive’s nice surprises: an unpublished story called “… Coming Closer …” based on her relationship with Jim Morrison.) I was overwhelmed with curiosity about what her papers might reveal. What could the personal documents of a writer who was so public about her private world teach us about her work? How much of that persona was a performance and how much a reflection of her real anxieties and ambitions?

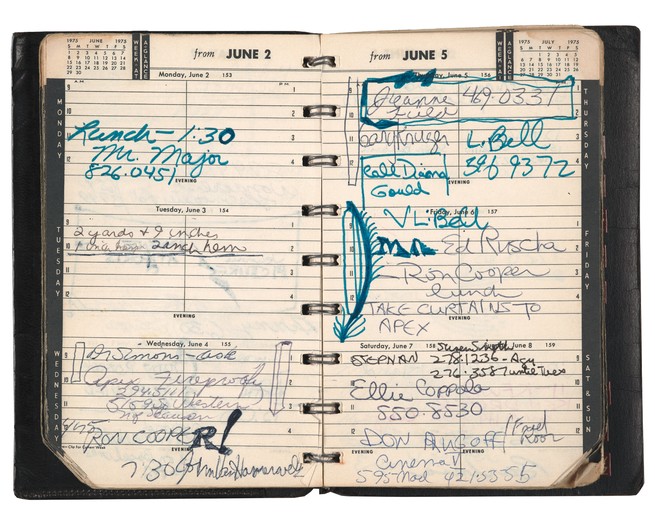

One of the oddities of the archive is that when it comes to her letters—I spent time in just two boxes, which mostly contained correspondence—one doesn’t know whether any of these notes were ever sent to their putative recipients: These are not carbons but original drafts, many of them signed. Babitz comments elliptically on this peculiar epistolary practice in a letter to her friend Carol Grannison-Killorhan: “Today I’m going to mail the letter I write to you instead of sticking it into a file of unmailed letters I’ve started because they’re practically a diary.” I read this, of course, in a file of unmailed letters.

If you know three things about Babitz, you probably know that Joan Didion gave her her first big break as a writer. Babitz’s actual friendship with Didion and her husband, John Gregory Dunne, was more complicated, however, as friendships always are. A little over halfway down the second page of the eight-page (!) dedication in her first collection, Eve’s Hollywood, Didion and Dunne get a pretty sideways thanks: “And to the Didion-Dunnes for having to be who I’m not.” Just ambiguous enough to be glossed over? But privately, Babitz nursed some old wounds: In an undated note from the early 1980s, she remembers, years earlier, “John [Gregory Dunne] asking if Dan [Wakefield, a boyfriend] had written my stuff.”

In an extraordinary letter, likely from 1972, that was almost certainly never sent, Babitz takes Didion to task for hiding behind her various forms of privilege in order to opt out of feminism. The letter begins with Babitz voicing her frustration that she can’t get Didion to read Virginia Woolf, and proceeds to deftly turn the argument of A Room of One’s Own against her: “For a long long long time women didn’t have any money and didn’t have any time and were considered unfeminine if they shone like you do Joan.” Didion benefited from the ways that the literary establishment changed in response to Woolf’s critique, Babitz suggests, but Didion is unwilling to acknowledge the debt or pay it forward. “And so what you do is live in the pioneer days,” Babitz continues, “putting up preserves and down the women’s movement.”

Part of the reason that Didion can do without feminism, Babitz suggests, is that the 5-foot-2, 95-pound Didion didn’t loom as a physical presence—didn’t make men uncomfortable. “Just think, Joan, if you were five feet eleven and wrote like you do and stuff—people’d judge you differently and your work,” Babitz writes in that same letter. “Could you write what you write if you weren’t so tiny, Joan? Would you be allowed to if you weren’t physically so unthreatening?”

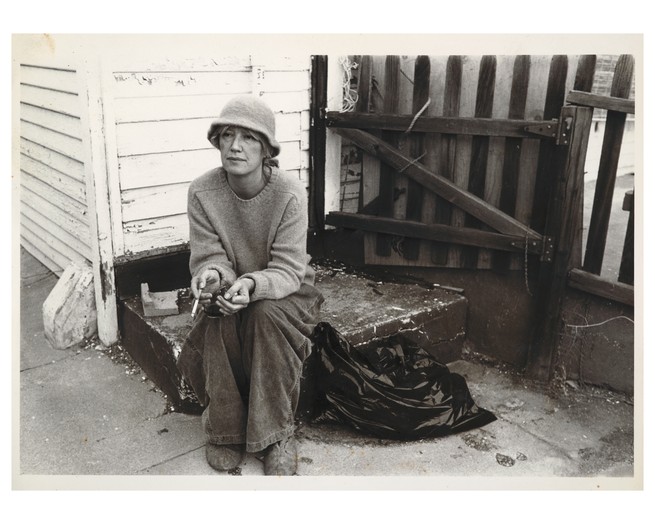

Babitz was four inches short of that 5 foot 11, but she had other attributes that made her presence, and her femininity, impossible to ignore. Her most explicit attempt to address this challenge was “My Life in a 36DD Bra, or, the All-American Obsession,” a piece she wrote for Ms. in April 1976. Babitz felt that the disembodied prose of Didion simply wasn’t possible for her. Evidence of her bodily self-consciousness punctuates the correspondence. In an undated manuscript, she suggests that, as a woman working in the music industry, she’s every bit as threatened by typecasting as a Hollywood starlet: “I’m just a sex symbol, nobody thinks I can really act just because I took my clothes off in my first movie!” In a 1972 letter, she wonders why men so freely dismiss her: “Big tits, I suppose, they think they have a right because of that.”

Babitz’s response to this situation was characteristically complex. It’s summed up in the two-sentence letter of introduction she sent to Joseph Heller in 1961: “I am a stacked eighteen-year-old blonde on Sunset Boulevard. I am also a writer.” As a grammar nerd would tell you, it’s the parataxis that’s doing the interesting work here: I’m both of these supposedly mutually exclusive things, and I insist that you acknowledge both; neither is subordinate to the other. Wrap your head around that. Not surprisingly, her correspondence is full of references to Marilyn Monroe and Babitz’s anger at the men who surrounded her who, dazzled by Monroe’s sexuality, would not take her seriously.

A series of letters from the fall of 1972 comment on her relationship to her body and its effect on her sense of self. Her concerns about her weight, and her adoption of various diets, are mentioned across the entire corpus of the letters—but that fall, she took up running and began to see results in both her waistline and, more significantly, her legs. In “My Life in a 36DD Bra,” Babitz deploys the “leg man/tit man” binary to her own shrewd rhetorical ends, but in these letters, she’s thrilled that getting in better physical shape means getting recognized for her legs (which in one letter she likens to Betty Grable’s) rather than her breasts. Her breasts (“tits,” she frequently insists on calling them) were given, not made; those toned legs were something that she had created herself. If she was going to be admired for what evolutionary biologists call “supernormal stimuli”—and from the age of 15, she knew that she would be—she preferred that it be for what she’d labored for rather than what she’d simply been blessed (and cursed) with.

It’s clear that throughout her career, Babitz’s writing was underrated (or ignored) by powerful men in the publishing industry. Often, it was dismissed as “gossip.” In an undated letter to Heller, she thinks through the gendered implications of that term: “‘Serious’ people just don’t think that gossip, the specialité de ma maison, is ‘serious.’ Whereas I know that nothing on earth overjoys people the way gossip does. Only I think that because it’s always been regarded as some devious woman’s trick, some shallow callow shameful way of grasping situations without being in on the top conferences with the ‘serious’ men, the idea of ‘gossip’ has always been considered tsk tsk. Only how are people like me, women they’re called, supposed to understand things if we can’t get into the V.I.P. room.” Gossip, Babitz suggests, is a different, subaltern way of knowing—disdained by the (male) structures of power, but with a power (and an appeal) all its own.

One of Babitz’s characteristic habits of thought is not to reject such criticism, but to embrace it. In a 2000 letter introducing herself to a new editor at the Los Angeles Times, Babitz writes, “Basically, fun is my subject—and I can at least make some attempt to write about Los Angeles as interesting, no matter what bad things they say about it in more civilized quarters of the world, where they know they’re right.” Writing to the Rolling Stone editor Jann Wenner, she explains the fundamental mistake that the editors of his Los Angeles Flyer project are making: “See, those guys insist that they want hard news, but what they don’t understand about Los Angeles, is that we don’t like news, we like artifice.” Indeed, in one letter to a friend, Babitz goes further, essentially denying that gossip is distinct from information and data: “My friend Earl says I like information too much. Data. But I love data and information—it’s such a ballet—it’s such a morality play—everything is always so perfect and people seem to be dancing in the same mirrored ballroom where—like a kaleidoscope—just when you think every thing’s falling apart—it’s just going into another beautiful design.” Gossip is made in the eye of the beholder.

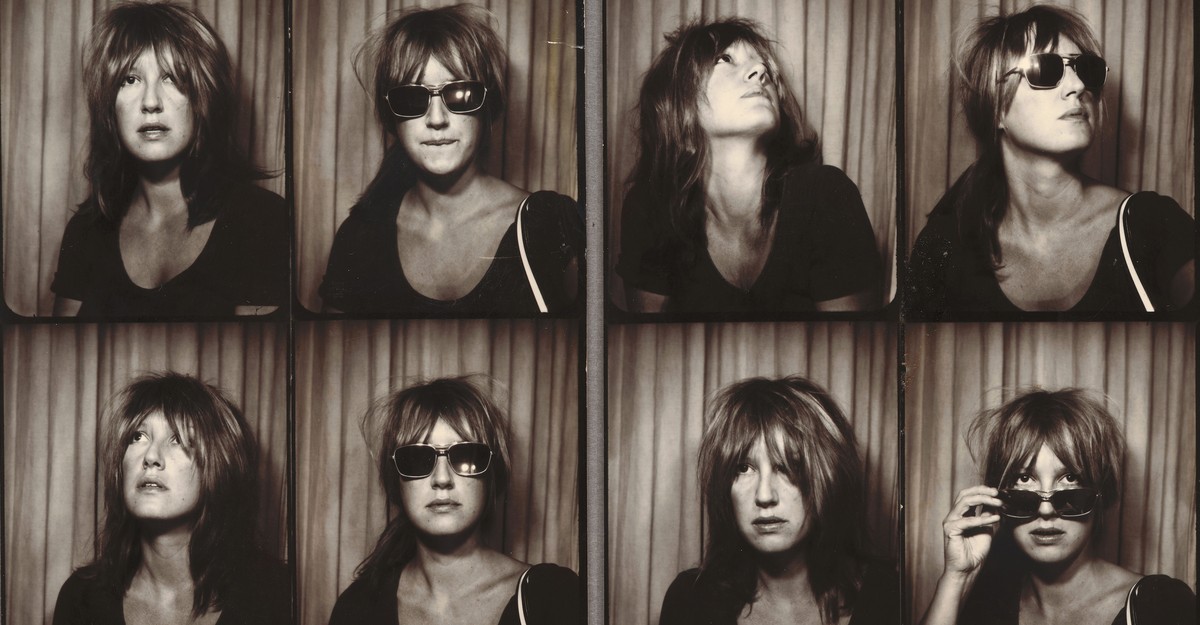

“Information”: those 22 bankers boxes contain lots of information, both data and gossip. But as one sits in the Huntington’s Ahmanson Reading Room, poring over files and folders and photos, something even more interesting, “another beautiful design,” gradually emerges: a portrait of an artist in the process of inventing herself. If the first page of a Google image search is littered with Babitz playing chess with Duchamp, here, we’re privileged to look in on Eve Babitz playing a character called Eve Babitz, in the way that Oscar Wilde fashioned, and then played, Oscar Wilde. Most thrillingly, perhaps, this is what the archive as a whole delivers to its readers: an experience of watching Eve Babitz drafting, revising, perfecting, becoming.