How The 2010s Killed The Celebrity Gossip Machine

Back in the winter of 2011, I was sitting in my tiny apartment in Austin, Texas, finishing my dissertation on the history of celebrity gossip. Starting all the way back at the beginning of what we now know as Hollywood, I traced the evolution of how stars were created, packaged, sold, and consumed, from Mary Pickford through Britney Spears.

But writing a dissertation is dull, solitary, deeply unglamorous work, and when a producer emailed me to ask if I’d be in a documentary about “the business of celebrity,” I jumped at the chance. They flew me to New York, filmed me at Sarah Lawrence to give me the “aura” of an academic, and asked me questions about the past and present of celebrity. If you’ve never been part of a documentary, you likely don’t realize just how many times the “talking heads” get asked a question before landing on an answer the producer likes. “Can you answer that again, but much more condensed?” “Can you say the same thing, but with one word?”

I was deep in academia at the time, where answering with one word, about anything, felt like blasphemy. But they kept asking me leading questions about the effect of Perez Hilton, and the paparazzi, and TMZ: “How have they made life hell for celebrities?” “Can you talk about how they’ve ruined celebrity?”

My responses weren’t just too long, they were too unemotional. I viewed the rise of the digital paparazzi, and the gossip blogs built alongside them, in less moralizing terms. This was simply the latest pendulum swing in a century of oscillations in celebrity power. At the end of the 2000s, celebrities had found themselves largely beholden to the seemingly ever-growing swarms of paparazzi, forced to remain vigilant about how and when they appeared in public, terrified that a snippet of unflattering, unbecoming, or straight-up scandalous footage would make its way to TMZ.

Which is why the producers of the documentary kept asking me the same questions. They wanted something closer to the thesis of their film: that Perez, and amateur paparazzi, and TMZ, and the voracious appetites for content they both sparked and satiated, were ruining celebrity. It wasn’t until the film came out, a year later, that I realized the reasoning for the thesis: The film’s executive producer and director (absent the day of my filming) was Kevin Mazur, who’d spent decades photographing celebrities for Rolling Stone.

Mazur considers himself a “good guy” in the industry: the sort of guy celebrities trust, who they invited into their home, who’d never publish a photo that was unflattering or unsanctioned. Which is how he convinced Jennifer Aniston, Jennifer Lopez and then-husband Marc Anthony, Elton John, Kid Rock, and Salma Hayek to participate in the film as well, describing the paparazzi’s tactics, from the general hounding on the street to the use of helicopters to catch footage of Lopez and Anthony’s backyard wedding ceremony. Their argument, like that of the film, was ostensibly that the business of celebrity had become exploitative and dangerous for the celebrities themselves — which, given the rash of car crashes as celebrities fled brazen paparazzi, was true. The industry itself was broken, transformed from a system of honor and veneration into one of shame and denigration, which treated its products as little more than commodities to be bought and traded.

Spencer Platt / Getty Images

A subway newsstand in Brooklyn.

In many of the interviews for the documentary, I attempted to point out that this wasn’t the first time that this had happened. What’s more, the real anxiety wasn’t necessarily over the fact that celebrities were being treated as commodities — they always have been! — but that the celebrities, and the apparatus they pay to protect them, were feeling something they hadn’t felt in some time: out of control and, as such, out of power.

What began in the aughts came to a head in the 2010s, as celebrities, publicists, and the various outlets they collaborated with, from People to Entertainment Tonight, scrambled to combat narratives generated by those outside the established Hollywood system. They were pissed, and they were scared, and rightly so — the internet, and the masses of amateur photographers, content generators, and gossip sites were fickle in their affections, unpredictable in their turns. Someone as apparently beloved as Tom Cruise had quickly become an internet punchline overnight, simply by doing the same shtick he’d been doing for the last 20 years — only at the time, there was YouTube to remix the couch jump, and Perez Hilton, Lainey Gossip, and countless other gossip bloggers primed to lampoon his attempts at romance.

In the end, the solution was so straightforward. Celebrities simply became their own paparazzi.

And the options for defense were slim. You could play the paparazzi game — like Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt, purportedly arranging for photographers to “accidentally” catch them with their newly adopted daughter Zahara, playing in domestic bliss on the beach. Or you could play the paparazzi, appearing in the same outfit every time you went outside, and thereby driving down the price of a shot. Or you could move out of Hollywood, as Julia Roberts did to raise her twins. But to extract yourself from the paparazzi game was to extract yourself from a certain brand of fame altogether — something that some celebrities, like, say, Jennifer Lopez, could not afford.

But if this decade’s start represented one extreme of the celebrity power pendulum, then 2020 marks a return swing: The stars haven’t been this powerful, with this much leverage, since the 1950s, when they first broke free from their studio system contracts, or the 1980s and ’90s, when the rise of the power publicist and agent granted them unprecedented leverage. In short, no could ever make that documentary, with that argument, today.

But the celebrities didn’t vanquish the paparazzi so much as figure out how to undercut them — and the publications they fueled. In the end, the solution was so straightforward. Celebrities simply became their own paparazzi, posting all manner of details and footage of their daily lives on social media, and effectively put real paparazzi out of business.

Michel Dufour / WireImage

Gwyneth Paltrow holds her baby, Apple Martin, as they attend the ceremony for the Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur on Sept. 5, 2004, in Paris.

Back in 2004, after Gwyneth Paltrow gave birth to her daughter, Apple, she battled paparazzi around every London corner, all desperate for a rare shot of the baby — to the extent that Paltrow threatened legal action. When she gave birth to her son, Moses, two years later, she tried a different tactic. She simply stepped out the door, Moses cradled in her arms, and waited while the sea of photographers snapped hundreds of photos, effectively devaluing the photos, and decreasing the demand for more, at least in the short term. But Beyoncé and Jay-Z had an even better plan.

In August 2011, Beyoncé performed “Love on Top” at the MTV Video Music Awards — and at the song’s end, unbuttoned her suit jacket, pivoted slightly to the side, and rubbed her slightly growing belly. It was the Beyoncé version of a pregnancy announcement, which prompted what was then a record-breaking number of tweets per second on Twitter. When she gave birth, in January 2012, she and husband Jay-Z paid $1.3 million to rent out the entire fourth floor of Lenox Hill Hospital in New York to ensure total privacy.

Just two days after their baby was born, they released a public statement announcing the birth of a “healthy 7 lbs” girl named Blue Ivy Carter. And then there was nothing: no photos, paparazzi or otherwise, until Feb. 11, when they published five photos to…Tumblr. MeetBlueIvy.tumblr.com. It was the beginning of a total-control publicity strategy that extends to this day, whether on Tumblr, on Instagram, in Beyoncé-produced documentaries, or in Beyoncé-controlled magazine interviews and photo shoots.

The only rupture in Beyoncé’s immaculate personal narrative control came in 2014, when elevator surveillance footage of Beyoncé’s sister, Solange, attacking Jay-Z was leaked to TMZ. But it was one of the last moments of TMZ’s relevance — and instead of directly addressing what happened, Beyoncé simply dropped a remix of “Flawless” a few months later that alluded to the attack — “Of course sometimes shit goes down when there’s a billion dollars on an elevator” — while actually revealing nothing about its motivation.

Beyoncé is admittedly the most extreme example of a celebrity leveraging control over their own image. But the more appropriate description might be “gold standard”: there’s what Beyoncé does with her publicity, and then there’s everyone else trying to figure out their own version of it.

Christopher Polk / Getty Images

Beyoncé, Jay-Z, and their daughter Blue Ivy Carter attend the 60th Annual Grammy Awards on Jan. 28, 2018, in New York City.

The Kardashians, for example, have never shunned the paparazzi. But they’ve savvily used social media to extend the footprint of their existing reality television stardom (see: Kim posting footage of Taylor Swift okaying Kanye’s evocation of her in “Famous” on Snapchat). Kylie opted out of the Kardashian tradition of obsessive social media pregnancy documentation, refusing to even confirm that she was pregnant — until she announced the arrival of newborn daughter Stormi to Instagram, in a post that, until recently, held the record for the most-liked photo on the platform. An 11-minute video of her pregnancy, released to YouTube and titled “To Our Daughter,” has been viewed almost 88 million times.

Instead of relying on the gossip press — which, as 2000s and early 2010s coverage of the Kardashians makes clear, changes its posture toward celebrities from week to week — the extended Kardashian family figured out how to not only craft their own story, but profit from it as well. Publications often pay celebrities for “exclusive” shots and features of their newborn children, but now, celebrities can essentially bring the operation in-house — control the format, control the timing, and reap whatever YouTube advertising dollars and Instagram marketing potential that follows. (After posting the birth announcement, Kylie gained over 3 million followers in 15 days.)

Of course, the feeling of unedited, raw access is itself an illusion.

In the past, in the midst of a scandal or a breakup, celebrities would agree to interviews to tell “their side of the story.” Now, they just post an announcement online, either on their own celebrity brand website (as Paltrow did on Goop when she “consciously uncoupled” from Chris Martin), or via screenshots using the Notes app, iMessage, or whatever weird thing was happening with Channing Tatum and Jenna Dewan’s separation announcement. The Notes app, screenshotted and posted across a celebrity’s social media channels, has become the go-to method of public apology, for anything from collaborating with R. Kelly (Lady Gaga) to stranding thousands of people on an island without adequate food or shelter (Ja Rule).

The Notes app apology provides more space than a tweet, more personality than a publicist’s statement, and — just like everything else that comes out of a celebrity’s “personal” social media account — the aura of authenticity. A Notes apology, like an Instagram selfie, gives the audience a feeling of unique access to the “real” star, seemingly unmediated by the polishing hands of publicists, editors, and photoshoppers. It has the same root appeal of the paparazzi photograph: intimacy and access — only this time, controlled by the star themselves.

Of course, the feeling of unedited, raw access is itself an illusion. During the era of Classic Hollywood, press agents ghostwrote all manner of fan magazine articles “authored” by the stars; in 2009, Britney Spears and 50 Cent both openly admitted to employing “ghost tweeters” to maintain their brand. Few celebrities would confess as much today: Some get around the fact that half of the content is clearly run by their publicity team by marking self-authored tweets, like Tom Hanks does with “Hanx.” But as Lindsey Weber points out, any effective “apology” has gone through a publicist edit. Every photo has been touched up or facetuned. Every time a celebrity comments on another celebrity’s Instagram, it’s with full knowledge that it could become a story itself.

And that’s where the power dynamic has truly shifted. The gossip magazines and blogs used to manufacture their own narratives of good and evil, slights and backbiting, weight loss and gain, employing carefully selected paparazzi photos and “sources close to the star” to prove their point. Now, they simply reprint what’s happened on social media: a collection of “Celebrity Kids Meeting Santa” is actually just a roundup of Instagram photos; a story on how Jennifer Garner’s son promised to “always” be her date is just a reprint of a caption for Garner’s latest Instagram video.

Again, this strategy isn’t entirely new: Publicists have always seeded stories and exclusives with gossip publications, and Garner herself was known for appearing in public parks with her children following cheating rumors on the part of then-husband Ben Affleck, essentially inviting paparazzi coverage that would steer focus away from rumored infidelity. These days, Garner isn’t forced into calculated park appearances, or hoping her publicists craft an effective counternarrative in their negotiations with the gossip magazines, or that the right quotes from interviews make it into the feature-length magazine profile. Instead, she just broadcasts her “Pretend Cooking Show” on Instagram to her 7.9 million followers — a strategy that has proven far more effective in remaking her image, and disarticulating her from Affleck, than any formal publicity maneuver.

For all the control celebrities currently enjoy over their images, ruptures do still occur — usually, as before, via the release of unsanctioned paparazzi photos. But those scandals, like news of a breakup, can be readily repaired via social media, where every comment, “clapback,” and interaction is amplified through coverage in the rest of the gossip press. The entirety of a recent post on People.com, for example, reports that Justin Timberlake left a “flirty comment” on wife Jessica Biel’s Instagram, weeks after issuing a public apology (Notes app!) to Biel after he was “caught” holding hands with his costar during a night out in New Orleans. The paparazzi may have incited the so-called scandal, but its resolution plays out entirely on the star’s terms.

Gossip has always allowed us to speak the otherwise unspeakable.

When a celebrity is shamed for weight gain, they can counter, as Rihanna did in 2017, with a Gucci Mane meme that renders the entire conversation ridiculous. A celebrity can come out — as Frank Ocean did on Tumblr, back in 2012, or Lil’ Nas X did, in 2019, on Twitter — without having to appear on the front of a magazine with the headline “I’m Gay” accompanying an interview designed to appeal to mainstream America. Tabloid photos of aging stars used to cannibalize their images, transforming them into abject horrors. Now, Jane Fonda posts a photo of herself the morning after a red carpet appearance, still in her dress from the night before. Instead of “makeup-less horror can’t even take care of herself,” she gets to caption the photo herself: “Here’s me the next morning. I couldn’t get my dress unzipped so I slept in it. Never wanted a husband in my life until now.” Instead of an aging has-been, she’s “honestly so relatable.”

It’s difficult to complain, really, about any of these shifts: Once-banal celebrity images have become more interesting and delightful; there’s far less traditional gatekeeping on the part of the gossip industry and, as a result, the celebrity world in general has become less white, less straight, and less American-dominated than ever before. Hundreds of people lost a paycheck with the end of the paparazzi boom, but it’s hard to ignore that those paparazzi regularly put their subjects in danger. And while a major, old school, social-media-resistant star like Tom Cruise may still be able to open a global franchise, he’s the last of a dying breed.

Sure, celebrity profiles are far less interesting, and celebrity trainwrecks have been replaced by the trainwreck of American politics and an ever-growing number of scammy influencers. But when I look back at the peak of the ’00s gossip area, and the abject thrill of every new picture of Britney breaking down, I remember that the gossip had never been better — but it never made anyone, least of all Spears herself, feel good. Gossip has always allowed us to speak the otherwise unspeakable, working through understandings of sex and femininity and sexuality in a space “distant” from our own. But the power of the paparazzi in the ’00s, and the relative powerlessness of the stars, drove home a difficult truth: No matter how much distance between us and the stars, the intimacy we crave has very real psychological costs, especially when extracted without consent.

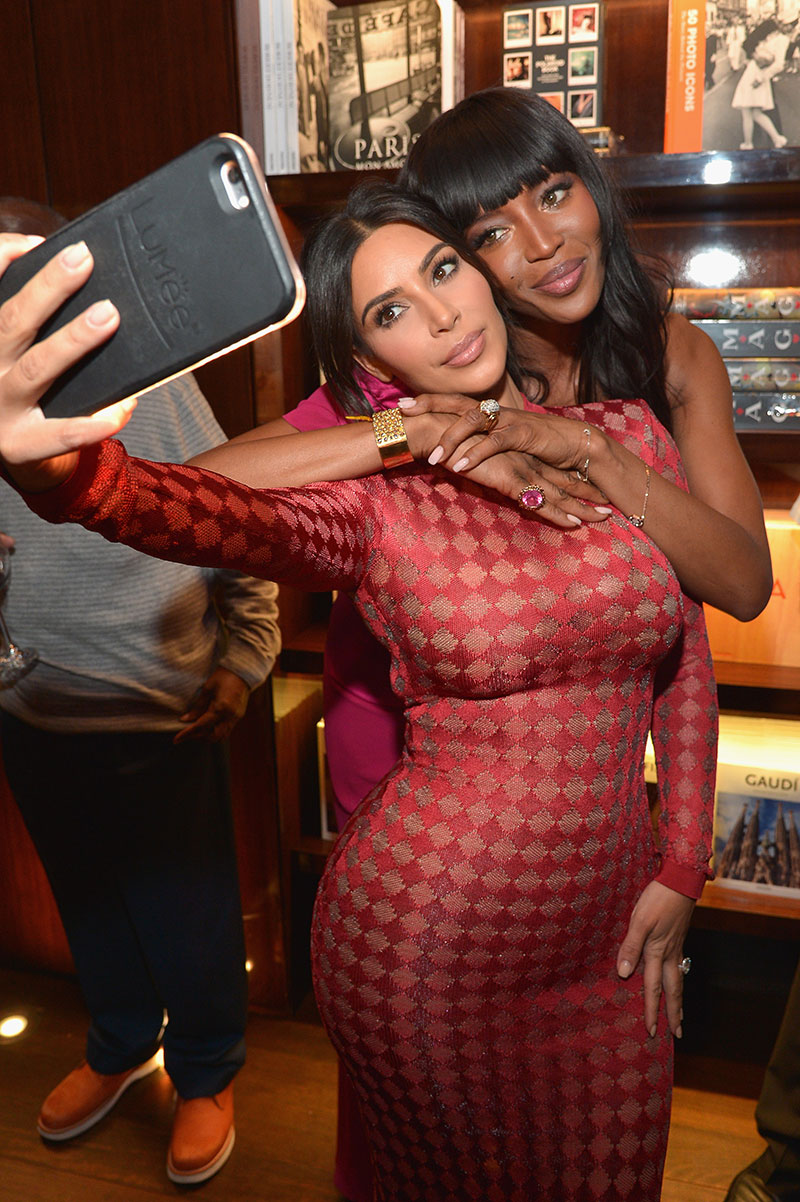

Medianews Group / Getty Images

Kim Kardashian West takes a selfie with a fan in Costa Mesa, California, on Dec. 4, 2018.

Celebrities of superlative talent will always be able to allow the work, and intermittent interviews about it, speak for itself. For everyone else, the current strategy is to let social media speak for you — and use it to keep the conversation going, even when the “actual” work is disappointing, or there are no more cute babies to post. It’s the way to maintain interest, to stay relevant, to launch and maintain a celebrity brand — to publicize the commodity that is the self.

It’s hard to believe now, but back in 2009, Ashton Kutcher was the most prominent celebrity on Twitter. He was the first to reach 1 million followers and the first, at least to my knowledge, to really understand what he could with the medium. On vacation in Turks and Caicos with then-wife Demi Moore, he posted a “twitpic” (lol) of Moore, taken from behind, as she leaned over in a pair of white briefs. The next month, he and Moore posted shots — and short video — from backstage at the Oscars. All of this seems so mundane now, but at the time, it was startlingly novel. The pair had spent years being hounded by the paparazzi. Now they were taking it back.

Turning the paparazzi gaze on oneself might offer the semblance of control. But the appetite it arouses remains the same: constant, nearly impossible to satiate, always wanting more. More content, more confession, more members of the family, more drama. And that hunger transforms celebrities into primary exploiters of their own lives. This will sound familiar to anyone with even a glancing relationship to fame. Surveillance by others turns into self-surveillance; anxiety over what to wear when you go out to the grocery store expands into what to wear and how to document that same trip to the grocery store in a way that seems different, and interesting, and special.

In 2010, Instagram had just barely launched; Snapchat didn’t even exist. No one — not me, with my 400-plus-page dissertation on celebrity gossip, not the stars themselves, not even the celebrity photographer who produced that documentary — could see just how powerfully the levers of power would shift in celebrities’ favor. But a decade later, the landscape of celebrity seems almost unrecognizable from the one I was asked to describe on-camera back then.

Celebrity or not, feeling a lack of control is exhausting and psychologically unnerving, if not permanently damaging. But so is its inverse. The stars who came of age in the ’00s and early 2010s are still haunted by living through a period of unyielding, unpredictable, incredibly invasive surveillance. But the celebrities of today are living through the same — and will someday have to grapple with the fact that they were forced, implicitly and explicitly, to do it to themselves. ●