Kim Kardashian for president! How my obsession with reality TV got out of control | Reality TV

My mum is watching TV in the kitchen, my dad is at work. The house is quiet. I assess: the TV is booming from the kitchen. My mum will be in there for a while. I switch channels. There is a naked woman on screen, covered in clay, pressing herself against a wall. I am not meant to be watching this. I look nervously at the kitchen door and turn the volume down. Her lips move but the words are inaudible. Now more people are getting naked and rubbing clay on breasts, thighs, genitalia. They jump up and down and cheer. They squish themselves against the wall like flies on a windscreen. I scoot closer to the TV. My chest rises and falls with the shallow gasps of someone so transfixed that they forget to breathe. I am 11 years old, watching a Big Brother pottery task get out of hand in the year 2000. My two decade-long love affair with reality TV is about to begin.

Reality TV has been a constant companion throughout my life. As a pre-teen and then a teen, I watched all the hits: Big Brother, Popstars, Pop Idol, The X Factor, The Simple Life, but also lesser-known dross: Newlyweds, I’d Do Anything, Wife Swap. The Pop Idol final between Gareth Gates and Will Young was as seismic an event in my school playground as 9/11 or Diana’s death.

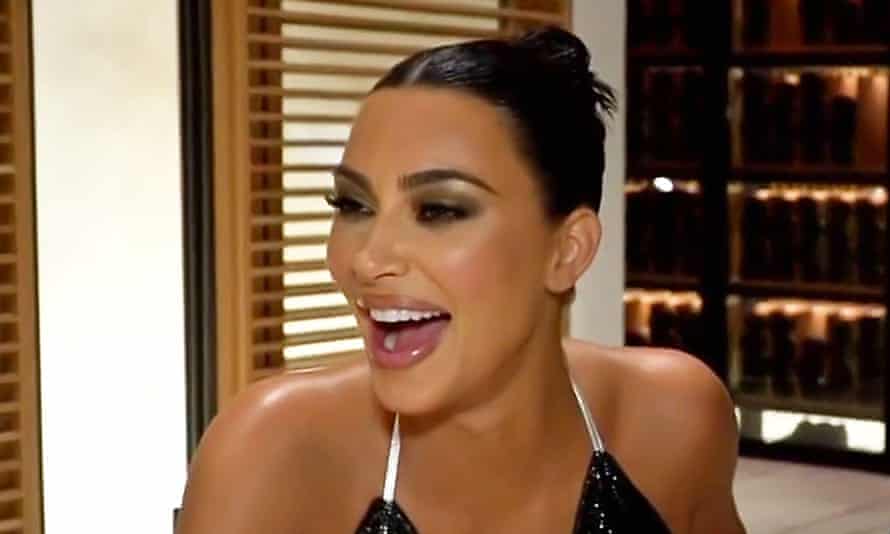

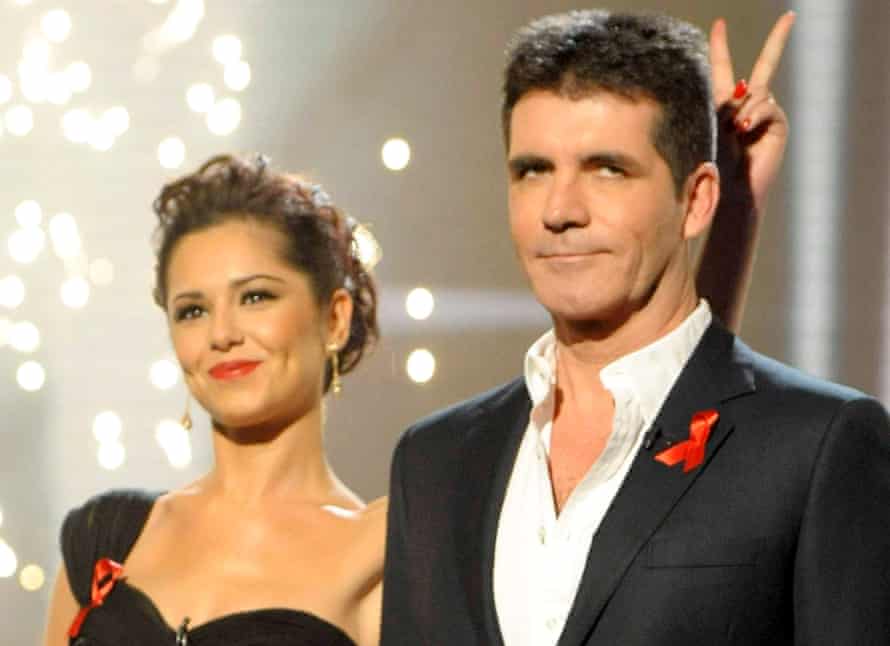

In adulthood, reality TV fuelled bad decisions. Aged 21, I dyed my hair the same cherry-red as Cheryl Cole’s when she was an X Factor judge. I ended up in the hairdresser the next day sobbing, having it stripped out. My 20s were lost to Keeping Up With the Kardashians, as I watched Kim ascend to the apex of reality TV fame in snakeskin booties and a Michael Kors handbag. I bought false eyelashes to look like these glamorous sisters with raven-black hair. Now, in my 30s, I glug The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills like a lab rat hooked on sugar water. Watching the housewives shriek at each other in a Hollywood Hills mansion has a wonderfully calming quality. I like to lie in the bath after a long day and watch them fight.

So when I began researching my forthcoming BBC Radio 4 podcast Unreal, co-written and co-presented with the journalist Pandora Sykes, I thought I knew how the story would shake out. I envisaged a lighthearted recap of my favourite shows, accompanied by deep dives into unresolved questions that linger to this day. (Like: did The Hills’ Lauren Conrad really have a sex tape, or did her frenemy Heidi Montag leak the rumour to generate a storyline? Or: whatever became of the contestants carved up by surgeons on grisly makeover show The Swan? And is the Kardashian Kurse to blame for the misfortune that befalls every adult with an XY chromosome who enters their orbit?)

But what emerged was a dramatically different story. Reality TV has never enjoyed the same critical celebration as other formats, despite its commercial success and innovative production values. When The Only Way is Essex beat Sherlock and Downton Abbey to win a Bafta in 2011, cameras panned to Sherlock actor Martin Freeman’s expression of quiet consternation. Reviewing Keeping Up With the Kardashians when it launched in 2007, the New York Times announced that it was about “desperate women climbing to the margins of fame.” Fifteen years on, Kim Kardashian is a billionaire, prison reform activist, and former Keeping Up executive producer Farnaz Farjam told me when we spoke that she wouldn’t rule out a Kardashian run for elected office. If fellow reality star Donald Trump can do it, why not Kim? Her 299m Instagram followers would surely help.

I suspect that this sneering condescension towards reality TV is partly class-based, partly gendered. Reality TV is a demotic form of entertainment – no opera lorgnettes here! – and it has offered a route into the entertainment industry for many people from working-class backgrounds. Jade Goody was the first, of course, but also Rylan Clark, Alison Hammond, Gemma Collins. And it’s a historically female-dominated genre, with many of the most successful shows of the past two decades led by female executives (such as Farjam, and Sarah Dillistone who worked on Towie and Made in Chelsea), or predominantly populated by women (like the world-conquering Real Housewives franchise, with 32 spin-offs and counting). I couldn’t begin to tell you the amount of times I’ve had to justify my ardour for reality TV to men who think nothing of watching people ride bicycles very fast in circles all day long.

How do I love reality TV? Let me count the ways. I love the humour: Amy Childs vajazzling Sam Faiers with a Carry On wink. Curtis Pritchard claiming that he really, really wants to make his fellow Love Islanders coffee in the morning to get out of cuddling the girl he’s coupled up with. The Celebrity Big Brother housemates getting confused and thinking that David Gest is dead, wrenching back the covers only to see the bemused TV producer sleeping soundly. I love the way the Real Housewives gives space to women in their 50s and 60s – who are so typically run off our screens – and allows them to discuss common female anxieties about ageing and infidelity. I love the intrigue, and the drama, of course – who doesn’t? – but also the way reality TV can communicate serious messages to the general public. After Jade Goody was diagnosed with cervical cancer in August 2008, while appearing on Big Brother India, an extra 400,000 women attended their screening appointments.

But in recent years, I’ve begun to feel conflicted about my passion for the genre. In 2020, information started leaking out about the effects of fame on The X Factor contestants. Former contestant Misha B said she felt suicidal after appearing on the show, specifically after judge Tulisa suggested she was a bully. Rebecca Ferguson, who came second in 2010, said that, after leaving the programme, she was forced to keep working on her music career while suffering a miscarriage. “For those who say you knew what you were getting into! I almost died promoting music for you all to listen to! Nope definitely did not! ever! In a million years sign up for that!,” Ferguson posted to Twitter. The irrepressibly bouffant-haired twins Jedward got in on the act, saying that their “biggest regret in life was not telling the judges on X Factor to f*ck off”, and that every contestant was a “slave” to the show who got paid “zero” while producers made millions. Suddenly, all those Saturday evenings I stayed in, humming along to a pre-fame Little Mix, hit differently.

Also in 2020, Love Island presenter Caroline Flack died. Hers was the fourth suicide associated with the show: two ex-contestants, and one ex-contestant’s boyfriend, had also killed themselves in recent years. Watching last year’s cohort of young, genetically blessed islanders tan by the pool, I felt complicit in something murky. My suspicions about the damaging effects of post-Love Island influencer fame were confirmed when I interviewed 2021 contestant Jake Cornish for the podcast. Trolls had threatened to murder him in front of his infant niece. Cornish was all masculine bluster – he was unaffected, he insisted – but not everyone has such a thick skin, nor should they. What happens to the contestants who can’t cope with this sudden, acrid fame?

There are no two ways about it: creating an entertaining reality TV show, and an ethical one, can be irreconcilable objectives. Historically, audiences have wanted conflict, even if it sometimes comes at the expense of contestants’ wellbeing and personal safety. (Who can forget the now-notorious “Fight Night” in Big Brother 5, which ended in security teams having to separate the warring housemates?) The Grecian pillars propping up the ornate marble roof of the reality TV Parthenon are conflict, producer meddling and editing. Frankenstein editing techniques make it possible to stitch together conversations that were never said. Off-camera producers manipulate contestants like twirling marionettes. (It’s worth remembering that Fight Night only took place because Big Brother producers showed housemates footage of other housemates talking about them, and plied them with alcohol. Still, the episode pulled in great ratings: so in producer terms, it was a win.)

But there are positive indicators that these pillars of exploitation are being chipped away by modern, socially conscious audiences. Last year’s Love Island saw a record number of complaints to Ofcom, who felt that Faye Winter’s expletive-filled outburst against fellow housemate Teddy Soares was, rightly, unacceptable. Aftercare has been strengthened on all major reality shows, although I’d question whether there’s a limit to what even the most stringent welfare package can achieve against the fetid roar of social media. And there’s an indication that audiences may be losing their taste for conflict, as a new crop of kinder reality TV shows surge in the ratings, like the delightfully bonkers The Masked Singer.

All of my criticisms, I utter with love. I have no more desire to see reality TV crumble than I have to stop the spring rains, or flowers growing. How could I disrespect the great house that has brought me such pleasure? But a few structural changes wouldn’t go amiss. Ethical producers; more rigid pre-filming checks; less salacious exploitation. I hope selfishly that these changes are made, and that in years to come you’ll find me curled up in the reality TV Parthenon still, watching the Housewives bickering under its great marble roof.

Unreal: A Critical History of Reality TV is on BBC Sounds from 17 May.

In the UK and Ireland, Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123 or by emailing jo@samaritans.org or jo@samaritans.ie. In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international helplines can be found at befrienders.org