The Frenetic Basketball Nostalgia of ‘Winning Time’

The 1980s Los Angeles Lakers were one of the most dominant teams in sports. At a time when professional basketball was on its heels, the Lakers brought new excitement: Magic Johnson versus Larry Bird, Jerry Buss and the glitzy Forum Club, and an up-tempo flow offense. That’s the story of HBO’s big-budget series Winning Time, whose Season 1 finale aired on Sunday, May 8.

David Sims, Vann R. Newkirk II, and Ross Andersen—three of The Atlantic’s biggest basketball fans—get together to discuss the series. What do they make of the accusations from former players that the show is inaccurately over-the-top? Does the producer Adam McKay’s style energize and streamline the show—or just add distraction on top of the glut of story lines? And how do you dramatize a history with a well-known outcome?

Listen to their discussion here:

The following transcript has been edited for length and clarity. It contains spoilers for the first season of Winning Time.

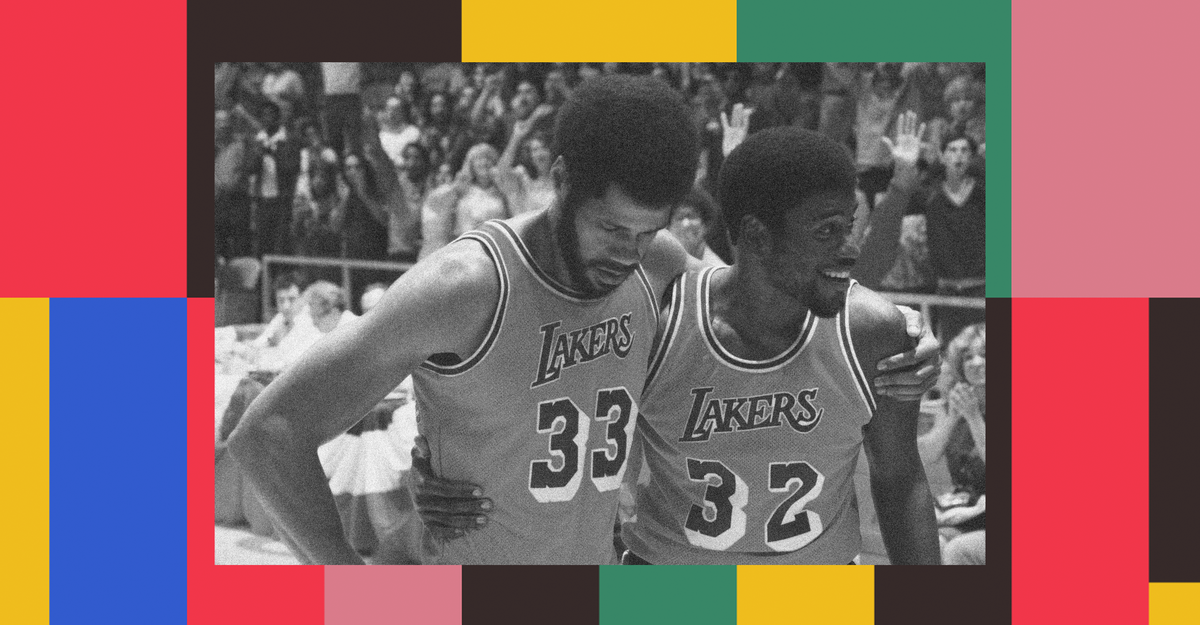

David Sims: We’re here to talk about Winning Time, the HBO series about the 1980s Los Angeles Lakers, whose first season just wrapped up. It’s set during the team’s 1979–80 championship season. And it’s about Jerry Buss. It’s about Magic Johnson. It’s about Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. It’s about a million other things. It has so many people in the cast. It’s got maybe a dozen major story lines that it’s jumping around on. It’s caused Jerry West to say he wants to sue HBO all the way to the Supreme Court. It’s one of the most hyped shows of the year. Were you guys pumped for it?

Ross Andersen: I felt like I was in The Truman Show and someone had made a special pop-cultural product that was just for me. I love the Showtime Lakers. That’s where my Laker love started. My kids both wear 32 in youth basketball for Magic Johnson. We are a Magic Johnson household. So yeah, I was pumped.

It’s also funny. I know we’re going to get into this a bit later, but a lot of the controversy about how these guys were depicted … I guess I didn’t fear that so much because, to me, a lot of this stuff seemed priced into their reputations already. I certainly didn’t have any fear going in that these heroic figures of my youth were going to be unmasked or anything like that.

Sims: Right? Plenty has been written over the years about the drama of the Showtime Lakers. It’s not like any of these figures are seen as innocent heroes, right?

Vann Newkirk II: I mean, the Jeff Pearlman book the show is based on is not not juicy. For my part, I was interested. Before I had kids, whenever I was bored, I’d turn on Hardcourt Classics, so this is obviously a show that’s tailored to my interests as well. As a Charlotte Hornets fan, I’m a big Lakers hater, so I also got a chance to see all the things about the Lakers mythology that I’ve hated forever. But I’m also a big Magic and Kareem fan. It’s hard to find more things in a show about basketball on HBO Max that are going to get me to watch.

Sims: This is exactly how I felt. I mean, yes, I’m a Knicks fan, not a Lakers fan. The Showtime Lakers are before my basketball-watching days, but it’s certainly the mythology you’re taught as you’re getting into basketball. So much of that mythology comes from around this time. When the show premiered and got kind of mixed reviews, the initial buzz was so much about what they’re getting wrong or why they’re telling something a certain way that I actually avoided it for a few weeks. Then I started binging it and found I did find it incredibly watchable. I don’t know how you guys felt, by and large, but it at least was always an easy thing to have on.

Newkirk: Yeah. I’ve never had a real urge to turn it off. And I have real reactions to lots of current TV. If I don’t like it, I really don’t like it. (Laughs.) I’ve always made the case for the comeback of mediocre TV. Regular TV. Average TV. And I feel like this was it for me.

Sims: Yeah, I would agree with that.

Andersen: Yeah, I found it eminently watchable. I don’t know if we’re ready to get into our deep impressions of the show, but it has left me surprisingly cool throughout, given the subject matter. I’m in the Venn diagram for the target audience. And I don’t know if that’s the sort of Adam McKay-ness of it—with the Instagram filters they’re using to retro-ize it ,which strikes me as weird—or what. I feel like one of the pleasures of period television is getting the cinematic treatment of an era that you didn’t inhabit. And so, seeing it through a kind of grainy VHS thing is weird. But on the flip side of that, the pace is really kinetic. I was never ready to flip away.

Sims: Yeah, the pilot is directed by Adam McKay, the Oscar-winning filmmaker. Everyone knows him from his comedies and then his more recent style that he shows off in The Other Guys and Vice, where someone would look into the camera all of a sudden and be like: “Hey, my name is Magic Johnson.” Or the film would switch with jump cuts for no reason. There’ll be a freeze frame. For instance, someone might say they’ve never done cocaine and there’s a freeze frame saying, “Oh yes, he did.” I’m making this up, but that is the general vibe, I would say. There was a time when that was different and intriguing, and now it’s gotten a little tiring. It’s especially tiring on a weekly television show, compared to a movie where you’re locked in with it.

Newkirk: Among Adam McKay’s work, it felt the most like The Big Short to me. And I think the things that did it for me in The Big Short, especially when they do the asides to explain all the complex financial mechanisms or whatever, is that you understand there’s a bit of magic there. You don’t really have to understand it to get the story. And I feel like that was a bad approach for talking about basketball. Do you really have to explain a fast break? You’ve got to have a little bit of faith in the audience. We’re not talking about CDOs here. We’re not talking about, like, credit default swaps. We’re talking about putting the ball in the hoop.

Sims: And we’re talking about the most famous basketball team of all time! Arguably. We’re not even talking about some obscure part of the NBA. This is Magic and Kareem. This is the Showtime Lakers. But, just to sort of give the basic setup, it’s about essentially Jerry Buss’s first season owning the team, Magic’s first season on the team, and the Lakers 1980 championship. (Spoiler: The Lakers won the title.)

It’s structured a little oddly. There’s a lot of setup about Jerry buying the team, about who they’re going to draft, about Magic fitting in, about the coaching situation. And this is always a challenge I find with true-story narratives. I know they’re going to draft Magic Johnson. I know that he’s going to be good. I feel like this show, especially early on, finds itself needing to juice things up wherever they can.

Andersen: I had the same sense. Even though I was super excited about the show, it didn’t really pick up for me until four episodes in, when they were in Palm Springs for training camp. The Jack McKinney story line, out of all the elements of the show, was probably the one I knew the least about. He’s the architect of the Showtime style of play. And the show portrays him as complicated: sympathetic in certain ways, but also kind of a jerk in others. That’s where it really came alive for me.

But, David, speaking of there being so many story lines in this show, it does seem like they don’t know what arc to pursue at the center of it, which is why I found that middle stretch of episodes, where we’re focused on McKinney and then the succession with Riley and Westhead, to be the most interesting sustained arc for me.

Newkirk: Up until Palm Springs, you’ve got, essentially, what I would say is a bunch of shorts about the Lakers. And then you get a little bit of narrative cohesion with how Showtime was actually built, which is what this season is about. And you hit all the beats: He’s a jerk. People aren’t buying into the approach. And then they realize that he’s got something there. And even as played and trite as that is, it works. It actually pulls together a story that’s not present in the beginning, but it also kind of falls apart at the end.

Sims: I’m just going to try to lay out the major story lines of the season. And I agree with you a bit, Ross. This show can’t quite settle on what it should be about. In my opinion, the Magic-Kareem dynamic is probably what it should be about. But I do think it’s just that there’s so much other stuff that it’s easy to get distracted by that they kind of flit around.

First, you’ve got Jerry Buss, played by John C. Reilly, who is the guy who bought the Lakers in 1979. There’s a story line about him building the plane in midair and trying to keep everything solvent and revamp the team. And you follow his mother, played by Sally Field, and his daughter Jeanie.

Then you’ve got Magic Johnson, played by Quincy Isaiah. His drafting; his future wife, Cookie; his sexual misadventures; his fitting into the team; you’ve got all that. You’ve got Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, who’s played by Solomon Hughes, who’s sort of the established star. He’s obviously one of the most famous basketball players of all time, and it follows him dealing with the fact that he sort of hates stardom, and he has a lot of problems with the way America is.

Newkirk: Fair enough.

Then you’ve got Jerry West, played by Jason Clarke, who is a former Lakers star and the old coach, who is eaten up by anxieties and insecurities. Then you’ve got Jack McKinney, played by Tracy Letts, the new coach who has this Shakespeare-quoting assistant in Paul Westhead, played by Jason Segel, and then Pat Riley, an old coach played by Adrien Brody. There’s so much going on, and I do feel like I’m missing stuff! It’s extremely overwhelming. There’s so much going on.

Newkirk: Paula Abdul is in the show.

Sims: Yes, right! The origin of the Laker Girls is even in it. The cast is incredible, and the amount of story lines they can dip into is as well. But the issue with the first season of the Showtime Lakers is that it doesn’t actually end with Magic and Larry facing off. The Lakers ended up playing the Philadelphia 76ers in the finals, so it can’t quite do the Magic-versus-Larry arc and maybe that’s why the show couldn’t quite settle down on one thing.

Andersen: Let’s talk about Kareem a little bit. I share your sense, David, that Kareem is one of the most interesting figures in American sports. Full stop. And the show doesn’t do much with him, actually. He has a lot of screen time. He never really does anything surprising. They settle into that sort of flat Kareem-as-unapproachable-captain thought.

Sims: Right. Especially in the first half of the season, he really is quite backgrounded.

Andersen: Yeah. And Kareem is someone who’s under-dramatized in pop culture. I wanted to see more out of that and don’t feel like I got it.

Newkirk: Yeah, as much attention as they’ve gotten about not being faithful to reality, this actually felt like a point where they were not taking risks, maybe in service of not getting people upset. I feel like he’s strangely flat. And to me that does feel like a symptom of them playing it safe. With that said, I do love how he seems to be upset at even being in the show.

Sims: What about Quincy Isaiah as Magic Johnson? Magic is presented as the opposite of Kareem. He’s always smiling, he’s happy, he’s cheerful. He wants to get the whole team involved. He’s just looking to have a party.

Newkirk: I do think his acting is invigorating. What dragged me through the parts of the show that I wasn’t too enthusiastic about was that I just really enjoy watching him play Magic. And on archetypal stories that resonate: somebody going to Hollywood, having to adjust, and getting caught up in the life is one that’s still interesting to me.

Andersen: Yeah, I thought Quincy Isaiah was pretty great. Sometimes casting for physical likeness can go disastrously wrong. I think this works really well. He does look remarkably like Magic, especially in profile. The actress that plays Cookie is also really incredible. As the season progresses, that’s where you saw Quincy Isaiah come alive, in those really intimate settings. Have you guys watched the new documentary on Apple TV+ about Magic?

It’s called They Call Me Magic. And you could tell from the title, it’s a five-hour commercial for Magic Johnson. Except, they do get pretty deep on the Cookie stuff and it makes the stuff in the show frankly look like hagiography of magic.

Sims: Everything about Winning Time is pretty peppy. Even when it’s dealing with darker or more fraught material, it’s still a very glossy, fizzy show. Even when it’s about Spencer Haywood struggling to stay alive and stay awake on the court. Do you think they thought it was just too dramatic? Too much of a bummer?

Andersen: The full depth of Magic’s portrayal unfolds over 10 years. And a lot of the most awful stuff hasn’t happened yet, to be fair, but they show him wrestling with it in a way that I think does Magic some favors in Winning Time. Whereas the documentary—which again, oddly, the rest of it is just like: Here’s Magic Johnson, the greatest winner that ever lived—does really go deep on the Cookie stuff in a way that’s really unflattering. I watched it with my 12-year-old son who worships Magic Johnson, and he was bumming about Magic after that.

Sims: I mean, Magic is quite open about that stuff. I guess, to his credit. And the thing you’re bringing up here, Ross, that I think is interesting is that this show has come under a lot of scrutiny for, “How close to the truth is it? How much is it inflating things just to create some drama for serialized television?”

But then on the opposite end, I do feel like sports documentaries are starting to tilt toward a lot of these things being produced by the person it’s about. Even The Last Dance in 2020, which was so much fun to watch, couldn’t quite escape the fact that Michael Jordan was deeply involved in its making. It was never trying to be like: “This is the real story and this is everything.” But when you’re working with the subject, you’re going to have that kind of conflict come up. Is there a way to chart a middle path on this?

Newkirk: Yeah, as much as I loved The Last Dance, it’s totally house-approved. And the reason it was so popular is because it tells us a story we already know and we get to relive it. We get to be nostalgic for it. It’s a narrative created by his team, by the NBA, by Nike and the Jordan brand.

We got to dip into that anthology. And that was what people needed at that time in the pandemic. And I think that’s actually sort of where a lot of these documentaries—not just sports documentaries, but just the form as content—collide and merge into one. We’re basically going to be injecting it directly into our brain stems soon enough. It’s the same way with the Kanye West documentary, Jeen-Yuhs. As much as I loved watching it, it was totally approved by Kanye. He’s a producer on the thing. The footage comes very intimately from him. You get the sense that, although it does run up against the controversies, if it had gone too far, it wouldn’t have ever seen the light of day. And that’s kind of the vehicle now. It’s very effective. But I don’t know if there’s a middle path.

Andersen: Yeah, and for people who aren’t NBA heads like the people on this podcast, The Last Dance did complicate the figure of Jordan for people who had only seen him as a kind of commercial symbol of excellence their entire lives. The Magic doc just doesn’t do that. As for a middle path, we see this in our tiny little industry. Stars have their own access to social media, so it’s hard to get them to sit down for something like a really objective magazine profile. It does seem like the trend is leading there.

Sims: The magic of The Last Dance is that, sure, you have to deal with Michael Jordan being involved in producing it, but you’re going to get this trove of footage that is just so compelling that it’s worth the access, right? Like that’s absolutely worth the access. But on the other side of things, you have Winning Time, where it’s fine to compress things or occasionally insert a character who’s a composite, like these sort of docu-shows and movies do all the time.

But with Jerry West, who’s someone who has talked in very real terms about the depression he struggled with as a player and as an executive, the show has him as this loud pain in the ass who was always breaking golf clubs and quitting in front of everyone. I do feel like it has to cartoonize him a little bit just to make things a little poppier. But are we losing something in that? I don’t know. He’s alive and can go out there and say it’s inaccurate. That’s fine. I don’t think the Supreme Court is going to be interested in this case, but what do you guys make of that aspect of things? Is it trivializing or is it just kind of necessary for good TV?

Newkirk: On the one hand, it’s good TV. Well, it’s regular TV, as I described earlier. There was no way, I think, to even justify including him in the story at this point if you didn’t have this part of the arc of his character. There’s no reason to be paying attention to Jerry West in 1980. He resigns. He’s out the door. They have a new coach. It’s Showtime. That’s the beat.

And if you want to have a reason to care about him when, spoiler alert, he comes back to the Lakers in the upcoming seasons, you have to establish some reason to care about him now. And so, just from a storytelling perspective, that’s how that cookie crumbles. He’s also right to be upset about it if it’s not true to his life. I would be upset about it if they made a fictionalized version of The Atlantic and I was throwing things out of windows. I wouldn’t love it, but that’s the medium.

Andersen: I was really sympathetic to Jerry West’s claims when I’d only seen the season opener. Those episodes weren’t my sense of Jerry West. But as the season progressed, I felt like they complicated his character in interesting ways and he actually comes across as pretty sympathetic.

Sims: Yeah, I would agree. It’s the early episodes where they had the biggest problem of needing complications, when the actual complications are not that severe. Jerry’s going to buy the team. Magic is going to get drafted. Kareem is the aloof kung-fu master who no one could really understand, and Magic is the happy, smiley guy who had too much fun sometimes. And Jerry is the guy who won the MVP of a Finals that he didn’t win. He’s the eternally tortured guy who only climbed the mountain once, so I understand why they slot him into the role he’s got as a slightly more tortured guy. But it does smooth out by the end. Everything in this show kind of settles down by the end.

Andersen: I just feel like Jerry is probably mad that they haven’t fast-forwarded to the scene where he traded Vlade Divac to Vann’s Hornets for Kobe Bryant.

Newkirk: Oh, goodness, I still dream about it.

Sims: The coaching thing though, you said, Ross, is the story I knew the least. I didn’t really know about Jack McKinney, who was the coach of the Lakers essentially for around 13 games in 1979. He installed the proto-Showtime system that’s going to become how they play basketball. It’s a more run-and-gun system. And then he injured himself in a bike accident and never really came back. He recovered, but was seriously injured, so he had all these memory problems. And the tactics of the Showtime Lakers were genuinely revolutionary, so I appreciate the show digging into that.

Andersen: Yeah, that’s right. If the NBA comes up at a dinner party, one of my famous trolls is to say that Magic Johnson is the greatest player ever. And the only real argument in my quiver is that he made the game beautiful. That Lakers team made it a game of flow and movement, as opposed to locking down in the half-court, throwing it into a big man, and then swinging around Princeton-style.

Newkirk: I wanted them to make more use of Dr. J. That was my main gripe. He is truly, to me, one of the most fascinating people in NBA history. Everybody focuses on the Magic and Bird rivalry. Everybody focuses on them as the two polar opposites in the league, which is good stuff. But also, I think there’s so much to wring out of Dr. J being the stylistic predecessor for Magic and Showtime, creating this brand of basketball that was considered to be too Black for mainstream viewers at the time.

Sims: “Too flashy.” “This isn’t how you play basketball.” Blah, blah, blah.

Newkirk: Yeah, I wanted more of that.

Sims: I get that if you’re making a show about the Lakers, you want Magic and Kareem at the forefront, but I would be fascinated by something that zeroed in on the nitty-gritty of the tactical evolution that’s going on behind the scenes. What McKinney thought about had to be revolutionary to a player like Kareem who did not play fast.

Andersen: What do you all hope for in Season 2? They leave us with a bit of a bread crumb with the Kareem-finals-MVP bit. They had resolved the kind of Kareem-Magic tension so utterly before the season even wrapped that you’re like: “Oh, there’s not much to wring out here in future seasons, because these guys now have total mutual respect and are perfect teammates together having heart-to-hearts.” And so they teased a little bit of how this conflict could reassert itself in the next season. Obviously, the Celtics are going to loom large because they’re going to have their moment in the sun. We’re going to get the ascent of Pat Riley. But what do we want to see in Season 2?

Newkirk: I do think Season 2 is going to have one of the most dramatic moments in Showtime history, which is, before Riley, we have to figure out how Westhead gets out the door.

Andersen: Yeah.

Newkirk: And that’s an absolutely bonkers moment in real life. So I think that’ll be fun.

Sims: And that’s something where, in retrospect, Magic sort of took the blame at the time and now it’s seen as more complicated than people thought.

Newkirk: That’ll be fun. We’ve got two more seasons of going against the Sixers before we even get into the Celtics drama though?

Sims: I have to imagine, since they’ve ordered a second season of this show, that Season 2 is going to have to compress things.

Newkirk: The next season, I think it’s unavoidable. They have to lose to the Celtics in the next season. It has to fast-forward to 1984. I don’t think there’s any viable way to tell the story without that being in the second season.

Sims: So it’s sort of the dark season of ups and downs with the Celtics on the rise.

Newkirk: Right.

Andersen: Well, this season opens with Magic at Cedars-Sinai, foreshadowing the HIV diagnosis. Presumably they want to land there. David, you know more about the business of Hollywood than we do, and the odds of this show getting to three or four seasons. It feels to me like you could see a three-season arc where they lose to the Celtics in ’84 at the end of Season 2, they come back and have the glory of the later championships, and then they end on Magic’s HIV diagnosis, his pivot to a new life, and ultimately the end of Showtime.

Sims: I would say at least three seasons. The show has been a ratings success. It’s had the kind of numbers I think HBO was probably really thrilled with, in that it’s grown its audience over the season. It didn’t open big and then shrink. It’s actually grown. So I have to assume that indicates good word-of-mouth. And this is a big glitzy streaming show that I assume costs a ton of money to make. This thing has a huge cast with a lot of famous people in it. Nothing about it looks particularly cheap.

So I don’t know. I wonder how you get the stakes feeling clear when we know the future of this team. But I also am someone who will flick on a 30 for 30 that I’ve seen before. There’s something comforting about taking trips down memory lane.